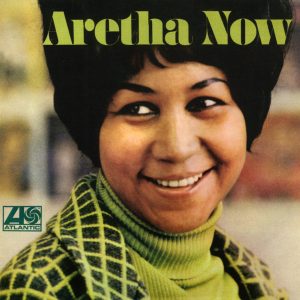

The videos of the great Aretha Franklin that have been posted at various places since her passing last week tell a fascinating story.

The videos are great musically, of course. But the higher level story is even broader than Franklin and her music. They show the brilliance of the American cultural machine. It creates a varied and rich national musical identity by gobbling up and integrating each individual genre, bit by bit.

It’s a game of give and take (which you can’t hurry, of course). In one direction is cultural appropriation. In the other, it’s that these cultures and the music they product gently — and, at times, not so gently — push all of us in the direction of that culture or musical genre.

The most obvious recent example of this is hip hop. The music started in the African-American community and gradually gained influence among suburban white youths. It’s now firmly part of our national culture.

The most obvious recent example of this is hip hop. The music started in the African-American community and gradually gained influence among suburban white youths. It’s now firmly part of our national culture.

Most people understand that this happens, but it’s worthwhile to think about once in a while. The passing of one of the people who set that dynamic seems to be one of those times. The process hits home when viewing two great videos, both of which feature Franklin and the equally great Ray Charles. The one at the top of this post is “Takes Two to Tango.” First and foremost, it’s just terrific. There is the song itself, the presence of the two stars and their obvious charisma and chemistry, how they are dressed and, to people of a certain age –which would be old — the fact that it was on “Midnight Special.”

“Takes Two to Tango” was written in 1952 by two Russian Jews: Dick Manning (who was born Samuel Medoff and changed his name when his writing career took off) and Al Hoffman, who was from Minsk (which now is in Belarus). We can assume his original name wasn’t Hoffman, though I couldn’t find out what it was. Hoffman, by the way, co-wrote “Mairzy Doats.” The two collaborated often, and their songs were performed by jazz greats. It’s light, bouncy and touches nothing of the deep meaning and soul for which Charles and Franklin were celebrated — or of Hoffman and Medoff’s heritage, which almost certainly included dodging Cossacks and Nazis.

The other video, below, is “Spirit in the Dark,” which features Charles and Franklin at about the same time performing at The Fillmore West in San Francisco. That performance tells a very different story.

The cultural appropriation goes both ways. Remember what “The Blue Brothers” was about: Two guys get out of jail and decide to reform the old band. Of course, the guys are white and most of band is black. The set-piece songs are fun — but tame and minus the hard edges of real blues. The movie is a time capsule of how three giants — James Brown in addition to Franklin and Charles — looked, sounded and moved at that point in their careers. The viewer only gets a limited view of what these folks really do.

The brothers themselves are voyeurs, moving from star to star without anything really important to do except play out the marginal story that tie the songs together. Throw in Henry Gibson as a Nazi and there you go.

Last week, Deadline Hollywood’s Mike Fleming Jr. interviewed John Landis, who directed “The Blues Brothers.” Landis said that musicians in the movie said that the film helped their careers in an era in which disco was king. (John and Danny of course refer to Belushi and Ackroyd):

LANDIS: What’s important to remember about that movie is, it was John and Danny’s intention to exploit their own celebrity of the moment, and focus a spotlight on these great American artists because rhythm and blues was in eclipse. To give you an idea, MCA Records, Universal Records, refused the soundtrack album.

DEADLINE: Why?

LANDIS: They said, who’s going to buy this music? And then, one of the great accomplishments of The Blues Brothers came when we recorded live John Lee Hooker on Maxwell Street, which is gone now. We had Pinetop Perkins, all these legendary people, recording John’s song “Boom Boom.” And when we ended up making a deal with Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun himself wouldn’t put John Lee Hooker on the album. He said, he’s too old, and too black. It was very gratifying when the album went platinum.

It would be discouraging, except that Charles, Franklin, Brown, Cab Calloway, Hooker, Perkins and lesser knowns such as Donald “Duck” Dunn, Matt “Guitar” Murphy (who died about two months ago), and Blue Lou Marini all got good paydays. Some certainly needed the money. It’s also not discouraging because the movie is a genial introduction to many younger people of the geniuses involved. James Brown really being James Brown would have been off putting to many folks.

The tug of war between the true experience and the watered down version that is close enough to the real thing to positively impact the evolution is a continually theme of music in general and American music in particular. Part of Louis Armstrong’s genius was packaging his talents in a way that was palatable to middle class white America. American jazz, which of course is most closely associated with African-Americans and their experience, found expression in Porgy and Bess. That is a jazz opera about the south written by two Jews of Russian and Lithuanian descent. Rock and roll is a repackaging and amplification of American blues by white Americans and Brits.

There is nothing here that is not pretty well understood. When a giant dies, however, it is interesting to consider that person’s path. In this case, Aretha Franklin was raised in the church and became a cultural icon by using her amazing skills to sing secular music. She pushed the culture — and the culture pushed back.

Add Comment