A few weeks ago, The Daily Music Break posted a news item on a survey conducted by the streaming service Deezer. The survey, which was reported upon at Business Insider, found that people stopped being open to new music when they are about 30 years old. The reasons are that people’s brains change and that they simply are too busy to explore. The idea is that music switches from being something people eagerly jump into and explore to something closer to a comfort food.

My guess is that the survey has it about right. There is another reason, however: Getting into new music in more than a superficial way is difficult – especially for people whose starting off point is rock.

Many of the people reading this post were raised on rock and roll. Since we lived it, the differences between the various sub-genres — and sub-genres within sub-genres — are intuitive. It also has a comparatively short history. Chuck Berry and Fats Domino, two of the grandfathers of the whole thing, were alive until last year.

The story is pretty simple. Jazz and blues slowly melded into early rock-and-roll. The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and the rest of the Brits came along, parallel rock cultures took root on the coasts and elsewhere in the United States and so on and so forth. It’s far more complex than that, of course, but that even such a rudimentary history is possible in one paragraph shows how simple it is.

But even that short history and the nuances between, for instance, English and American 1960s rock no doubt are difficult for a person jumping into it for the first time to master. That is a barrier to becoming a true fan. It takes work. Imagine not knowing that The Rolling Stones are more important than The Lovin’ Spoonful or that The Grateful Dead are from California and Lou Reed are from New York. If the nuance is not easy with rock, imagine the complexity of jazz or classical music, which have existed longer, have more varied roots, a longer list of VIPs and, less face it, a higher level of nuance and subtlety in the music.

The site A Passion for Jazz offers a timeline of jazz and blues from 1900 onward. There is ragtime, classic jazz, hot jazz (Chicago style), swing, Kansas City style, bebop, rhythm and blues, vocalese, mainstream cool, hard bop, bossa nova, modal, free jazz, soul jazz, funk, fusion, modern mainstream, Afro-Cuban, post-bop, a return of classic blues, acid jazz, hard bop revival, classicism, smooth jazz, jump blues, retro swing, jazz rap, M-base, traditional blues and European.

That list, which certainly has some intriguing names, seems to stop in about 2000. It also is likely that those categories are subjective. The point simply is that each of these types of jazz are different and a lifelong fan would know the differences. There is a lot to understand.

The same goes for classical music. mFiles.com breaks it down into early music, medieval/Gothic, Renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic and modern. What’s particularly interesting here is the dates. Early music is before the ninth century, medieval/gothic extends from the 9th to 14th century and so forth. That’s a bit longer than rock, isn’t it?

Of course, nobody has to know the story of classical music or jazz to listen to, appreciate and enjoy Aaron Copland’s “Appalachian Spring” or Charlie Parker’s “Yardbird Suite.” Both are timeless. At the same time, there is a certain level of intimidation. The feeling is that a person must be smart and sophisticated to really know what is going on. Most people will overlook that if the music is enjoyable. At a higher level, however, it doesn’t make the music endearing.

What is missing is the emotional tie. The analogy of music as comfort food illustrates the point. Somebody listening to and liking a song from a genre and artist with which they are deeply familiar is different than hearing something with which there is no emotional or sentimental attachment.

The Andrews Sisters and Vera Lynn were products of the tumultuous World War II era. People who were there will related to it different than people hearing it for the first time 50 years later. Kids hear The Who and Jimi Hendrix differently than their parents. This music is a bit harder to access emotionally for a person who didn’t live through the times. Likewise, contemporary music of a different culture or distant struggle will be based more on its perceived artistic merits than for a person with firsthand experience in that culture and struggle.

Clearly, structural changes to the brain and too much running around town are key reasons that people fall into musical ruts. Another very important factor simply is that it’s hard to become deep fans of new genres. The good news is that there are many ways to enjoy music, and listening to “Born to be Wild” for the thousandth time is just as legitimate as listening to “A Love Supreme” for the first.

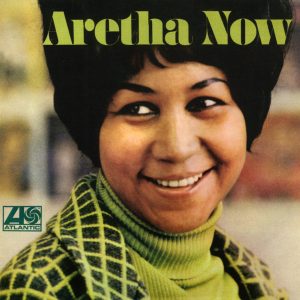

Above is Aaron Copland’s “Appalachian Spring,” conducted by Leonard Slatkin. Below is Charlie Parker’s “Yardbird Suite.”

Add Comment